Sacks Is Right: Socialism's Tax Onslaught Moves the ROI to Places Like Austin and Miami

California and New York are betting they can tax and scold tech and finance without losing them. David Sacks argues they’re wrong—and that Austin and Miami are where capital, innovation, and the future of American prosperity are already moving.

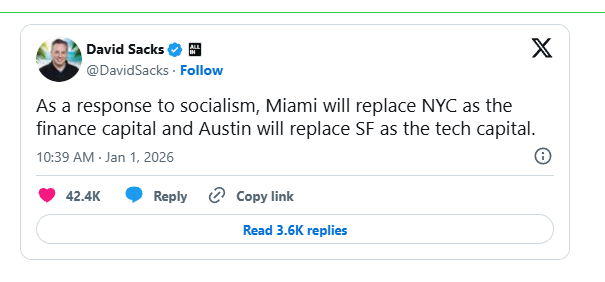

As a response to socialism, Miami will replace NYC as the finance capital and Austin will replace SF as the tech capital.

— David Sacks (@DavidSacks) January 1, 2026

All‑in Pod bestie, PayPal mafioso, and current Crypto/AI‑to‑the‑White‑House whisperer, David Sacks didn’t lob his New Year’s tweet into the void for sympathy from fellow billionaires. This came as California advanced a punitive “Billionaire Tax” ballot measure targeting ultra–high‑net‑worth residents and prompting open threats from tech leaders to leave the state. At the same time, New York City swore in its first openly democratic socialist mayor, who pledged in his inaugural remarks to replace “the rigidity of individualism with the warmth of collectivism.”

Sacks’s point wasn’t “feel bad for the rich”; it was that the people being cast as villains are the ones whose capital actually builds economies, while government merely taxes the results.

How wealth is actually created

The dominant political narrative suggests that if the government simply “asks a bit more” from the wealthy, nothing essential about the economy changes. California’s proposed billionaire wealth tax is built on that premise—up to a 5% annual levy on fortunes over $1 billion, including unrealized gains, stacked on top of some of the highest income‑tax rates in the country. New York’s top state rate hits 10.9%, New York City piles on a local tax, and long‑term capital gains are treated as salary.

Sacks’s objection starts with a basic observation: venture capital and high finance are as close to pure ROI engines as anything in the real world. Every dollar they allocate is judged by whether it produces more dollars. When you hit those dollars with new wealth taxes, higher income taxes, and ideological leadership that treats individual profit as morally suspect, you change where that capital chooses to live and work. Governments can only redistribute what investors and entrepreneurs first create—an echo of Adrian Rogers’s warning that “you cannot legislate the poor into prosperity by legislating the wealth out of prosperity.” History shows what happens when states ignore that reality: from the Soviet Union’s central‑planning collapse to today’s Venezuela, attempts to squeeze or control private wealth end up making people equally poor and starved of innovation, not equally prosperous.

From there, Sacks’s prediction about Austin and Miami stops sounding like provocation and starts looking like simple cause and effect. Punish capital in the cities that dominate tech and finance while rival states re‑write their laws to welcome it, and eventually the map shifts. The open question is how much damage is done before voters accept that.

How SF and NYC actually became powerhouses

San Francisco and New York did not become global capitals because a legislature ordained it. They rose because private risk‑takers discovered they were the best places to chase upside.

- San Francisco’s climb began with the 1849 Gold Rush, which turned the Bay Area into a magnet for traders, speculators, and capital. In the postwar era, Stanford‑trained engineers launched the semiconductor and computing revolutions in Silicon Valley, spawning Fairchild, Intel, Apple, and a tight cluster of venture firms on Sand Hill Road that still dominate startup finance. The Bay Area’s tech dominance is a product of that dense network of founders, engineers, and investors who came for profit, not for higher tax rates and wealth levies.

- New York’s financial crown grew from its harbor and the opening of the Erie Canal, which made Manhattan the choke point for trade and capital between Europe and the interior of a growing United States. The Buttonwood Agreement that birthed the New York Stock Exchange came from traders wanting a central market for risk, and over time banks, insurers, and hedge funds clustered there because that’s where deals were done.

In both cases, capital and talent arrived first; only afterward did government step in to skim and regulate the ecosystem. Sacks’s argument is that reversing that order—treating capital as a resource to be controlled first and cultivated second—will eventually reverse the outcome too.

What CA and NY are really signaling to capital

The fine print in today’s policy debates makes that reversal explicit.

California already hits high earners with a top marginal income‑tax rate above 12% and taxes long‑term capital gains as ordinary income. The “Billionaire Tax Act” would layer on a wealth levy targeting residents with net worth above $1 billion, counting unrealized gains and using “exit” and “look‑back” provisions to keep taxing people even after they move. Tech founders and investors have warned Governor Gavin Newsom through attorney Alex Spiro that they will permanently relocate if it passes, and high‑profile figures from Aduril's Palmer Luckey to David Sacks have publicly blasted the plan.

New York sends a parallel message. Its top income‑tax rate reaches 10.9%, New York City adds nearly 4% on top, and capital gains are taxed as ordinary income. The city’s new democratic socialist mayor reinforced that outlook with an inaugural speech promising to replace “the rigidity of individualism with the warmth of collectivism,” a clear signal that property rights and profit motives are not viewed as civic virtues.

Meanwhile, Texas and Florida are writing the opposite message into law. Texas has no state income tax and, with Proposition 2 (SJR 18), amended its constitution to permanently ban any state‑level capital‑gains tax on individuals, families, estates, or trusts. Florida has no personal income tax at all and aggressively markets that fact to firms and high‑earning individuals looking to relocate. To people whose livelihoods are tied to capital gains, those are not symbolic differences—they are hard constraints that determine where headquarters and portfolios move.

There’s also an uncomfortable variable that may come into sharper focus as more fraud and public‑fund mismanagement is exposed in states and cities—from Minnesota’s exploding nonprofit scandals to opaque local grant programs elsewhere: how many elites staying put are cushioned by corporatist arrangements that quietly subsidize their losses. In high‑tax, high‑regulation jurisdictions, politically connected firms often offset official rates with targeted subsidies, special contracts, and NGO‑mediated grant schemes that would never be offered to a new founder or small fund, blurring the line between “public service” and de‑facto kickbacks. As more of these arrangements come to light, it may turn out that the investors fleeing to Austin and Miami are the genuinely market‑driven ones, while some of those who remain are more entangled with the very public‑sector machinery that claims to be policing them.

The spin machine on defense

The defence of this policy direction isn’t coming from one grandstanding lawmaker; it’s supported by a full ecosystem of politicians, commentators, and friendly “explainers” who insist these changes are minor and morally necessary. CA Congressman Ro Khanna is one of the most visible examples. He has argued on X and in interviews that California’s billionaire tax is a manageable, one‑time charge that can be paid over several years, accusing critics of “glossing over” the details and implying that “paper billionaires” won’t really be harmed.

But the people who actually run money are saying something very different. Y Combinator CEO Garry Tan has warned that the California wealth tax is explicitly an unrealized‑gains tax: a unicorn founder valued at $5 billion on paper could suddenly owe roughly $100 million in cash to the state while being “illiquid,” a scenario he says will “kill startups and innovation in California.” In another exchange, Sacks urged Tan to open a YC office in Austin, arguing that treating Silicon Valley’s network effects as permanent is a “self‑fulfilling prophecy”—and that if funds and accelerators diversify into Texas now, they’ll create new hubs and regain leverage before politics “extracts as much rent as it can.”

AI expert Aakash Gupta, in a widely shared thread insisting San Francisco and New York will remain the tech and finance capitals, underscores how dominant the Bay Area still is in venture and AI—more than three‑quarters of U.S. AI investment, by his count. Yet that very dominance is what makes it such an attractive target for policymakers who see it as a captive tax base. Silicon Valley’s network effects are real, but they are exactly what invite the kind of extraction Sacks is warning about.

SF and NYC will remain tech and finance capitals.

— Aakash Gupta (@aakashgupta) January 2, 2026

Despite a few billionaires moving.

Here’s why.

For Austin to replace SF as the tech capital, it would need to capture the majority of US venture funding. In 2025, the Bay Area raised over $140 billion in VC. All of Texas raised… https://t.co/mUuJn8EMaV

The pattern is consistent: elected officials and others downplay the mechanics and cost of the new regime, while the founders, VCs, and allocators who have to find the cash spell out how destructive it will be. Sacks’s comments are aimed at that entire spin machine, not just one congressman.

Why Austin and Miami are the obvious heirs

Once you accept that capital responds to incentives, Sacks’s tweet about Austin and Miami becomes less a provocation and more a description of where many founders and funds already see their future.

Tech and VC: San Francisco vs. Austin

California still commands the largest share of U.S. VC funding. Data from NVCA/SaaStr and Carta show California companies capturing the majority of startup dollars, especially in AI, with the Bay Area alone pulling tens of billions annually. The ecosystem’s density is unmatched.

But Austin’s trend line is unmistakable. Founder guides and local data highlight multi‑billion‑dollar yearly deal flow, a growing bench of homegrown VC firms, and a surge of recently funded startups. Major relocations—including Tesla’s headquarters and Gigafactory near Austin and Oracle’s corporate move to Texas—have anchored a broader shift of engineers, operators, and suppliers.

If California continues to stack wealth taxes on top of high income‑tax and regulatory burdens while Texas constitutionally forbids capital‑gains taxes, the “marginal” founder or fund deciding where to build the next wave of companies will be pulled toward Austin. Silicon Valley still has more history; Austin has more future‑proof incentives.

Finance: New York City vs. Miami

New York remains the center of global trading volume, home to the NYSE, NASDAQ, and the headquarters or major offices of nearly every large financial firm. But South Florida has become “Wall Street South” at remarkable speed.

Local and national reporting describe an “[unprecedented]” wave of New York–based businesses and financial professionals relocating or opening major offices in Florida, driven by taxes, lifestyle, and remote‑work flexibility. Miami and its surrounding region now host dozens of international banks, hedge funds, and family offices, and the city’s 2025 economic outlook explicitly highlights finance and technology as core growth engines. Florida’s zero‑income‑tax regime gives every performance fee and bonus more after‑tax power than in Manhattan.

When a fund manager can move from New York to Miami, keep clients, drop state tax to zero, and still operate inside a growing financial ecosystem, Sacks’s prediction looks less like hyperbole and more like basic arithmetic.

Side‑by‑side snapshot

This is the landscape Sacks is reacting to. He isn’t claiming Austin and Miami have already replaced San Francisco and New York. He’s arguing that if policy trends hold, they will—and that pretending otherwise because old hubs still look strong on paper is exactly how you wake up one day and realize the network effects have quietly moved.

Why Sacks’s warning matters

You don’t have to cheer for Sacks personally to recognize what his argument exposes. The tech and finance elites being targeted by new taxes and collectivist rhetoric are the same people whose decisions about where to build companies, funds, and infrastructure shape the opportunities available to everyone else.

California and New York are effectively betting that they can keep raising the cost of staying—through higher rates, wealth taxes, and moral suspicion of individual success—without losing the people who made them rich. Texas and Florida are betting that, when forced to choose, those same people will prefer to be treated as partners in prosperity rather than as targets.

Sacks’s prediction about Austin and Miami is simply the logical endpoint of those bets. If California and New York keep squeezing the golden geese while denying they are doing so, the geese will leave. And as history keeps showing, you can legislate the wealth out of prosperity—but you cannot legislate prosperity back in once it is gone.

Sources

- California Billionaire Tax proposal

California Department of Justice, initiative text, “25‑0024A1 (Billionaire Tax).”

https://oag.ca.gov/system/files/initiatives/pdfs/25-0024A1%20(Billionaire%20Tax%20).pdf[1] - Coverage of California wealth‑tax backlash

- New York Times, “A Wealth Tax Floated in California Has Billionaires Thinking of Leaving,” Dec. 26, 2025.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/26/technology/california-wealth-tax-page-thiel.html - ABC7 News, “Tech moguls threaten to leave California as billionaire tax proposal gains support among unions,” Dec. 30, 2025.

https://abc7news.com/post/ca-billionaire-tax-proposal-peter-thiel-gavin-newsom-silicon-valley/18335032/ - Fox Business, “Tech billionaires threaten to flee California over proposed 5% wealth tax.”

https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/tech-billionaires-threaten-flee-california-over-proposed-5-wealth-tax - Business Insider / Yahoo Finance coverage of tech founders and investors reacting to the tax.

https://www.businessinsider.com/business-leaders-react-to-california-wealth-tax-proposal-2025-12

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/california-tech-founders-unload-proposed-182234751.html

- New York Times, “A Wealth Tax Floated in California Has Billionaires Thinking of Leaving,” Dec. 26, 2025.

- Khanna and political defense of the tax

- CNBC, “California’s Ro Khanna faces Silicon Valley backlash after embracing wealth tax,” Dec. 29, 2025.

https://www.cnbc.com/2025/12/29/silicon-valley-ro-khanna-faces-tech-backlash-over-wealth-tax.html - Webull / syndicated piece, “Ro Khanna Defends Billionaire Tax, Says Critics Are ‘Glossing Over’ Details.”

https://www.webull.com/news/14102171544667136 - Yahoo Finance, “Bill Ackman Blasts Ro Khanna For Defending Billionaire Tax: ‘Lost His Way.’”

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/bill-ackman-blasts-ro-khanna-133115005.html - Ro Khanna X posts (examples).

https://x.com/RoKhanna/status/2005090008584056993

https://x.com/RoKhanna/status/2005141934084403351

https://x.com/RoKhanna/status/2005440548723720243

- CNBC, “California’s Ro Khanna faces Silicon Valley backlash after embracing wealth tax,” Dec. 29, 2025.

- Tax‑rate references

- H&R Block, “California state income tax brackets and rates for 2024‑2025.”

https://www.hrblock.com/tax-center/filing/states/california-tax-rates/ - NerdWallet, “New York Income Tax: Rates, Who Pays in 2026.”

https://www.nerdwallet.com/taxes/learn/new-york-state-tax - Florida Tax Guide, “Taxes in Florida.”

https://www.stateofflorida.com/taxes/ - Deel, “Florida Income Tax Guide: Managing Taxes in a No‑Income‑Tax State.”

https://www.deel.com/blog/florida-income-tax

- H&R Block, “California state income tax brackets and rates for 2024‑2025.”

- Texas Prop 2 / capital‑gains ban

- Texas Legislature Online, SJR 18 (89th Legislature), enrolled text.

https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/89R/billtext/html/SJ00018F.htm - Texas Impact, “2025 Constitutional Amendments.”

https://texasimpact.org/2025-constitutional-amendments/ - League of Women Voters / voter guides on 2025 propositions.

https://www.lwvtexas.org/content.aspx?page_id=5&club_id=979482&item_id=126202

- Texas Legislature Online, SJR 18 (89th Legislature), enrolled text.

- Origins of SF tech hub and NYC finance

- SF Citizen, “How San Francisco Became the Center of Technology,” Oct. 9, 2024.

https://www.sfcitizen.com/how-san-francisco-became-the-center-of-technology/ - Investopedia, “How New York Became the Center of American Finance,” Jan. 3, 2024.

https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/022516/how-new-york-became-center-american-finance.asp

- SF Citizen, “How San Francisco Became the Center of Technology,” Oct. 9, 2024.

- VC geography and AI funding

- SaaStr / NVCA, “VC Deals in 2025 Off To Same Pace as 2024. And AI is 71% of All …”

https://www.saastr.com/nvca-vc-deals-in-2025-off-to-same-pace-as-2024/ - Carta, “California dominated the VC map in Q1 – VC geography.”

https://carta.com/data/vc-geography-q1-2024/ - Crunchbase News, “For Startup Funding, Every State Brings In A Pittance Compared To California,” Aug. 14, 2025.

https://news.crunchbase.com/venture/california-leads-startup-funding-2025-data/

- SaaStr / NVCA, “VC Deals in 2025 Off To Same Pace as 2024. And AI is 71% of All …”

- Austin VC ecosystem and relocations

- Visible.vc, “Top VC Firms in Austin: A Founder’s Guide to Fundraising 2025.”

https://visible.vc/blog/top-vc-firms-austin/ - Revli, “Updated List of Recently Funded Startups in Austin for 2025.”

https://revli.com/austin-funded-startups/ - WPTV, “‘UNPRECEDENTED’: Wave of NYC businesses heading to Florida” (also notes Texas moves).

https://www.wptv.com/wptv-investigates/unprecedented-wave-of-nyc-businesses-heading-to-florida

- Visible.vc, “Top VC Firms in Austin: A Founder’s Guide to Fundraising 2025.”

- Miami / “Wall Street South” coverage

- Fox Business, “South Florida cashes in on new wealth as New York City pays the price.”

https://www.foxbusiness.com/media/south-florida-cashes-new-wealth-new-york-city-pays-price - MiamiLocal, “Miami Economic Outlook 2025: Shaping the City’s Future.”

https://miamilocal.com/miami-economic-outlook-2025-thriving-industries-and-whats-ahead/ - Axis Space, “The Rise of Miami as a Business Hub – A Journey Through Innovation and Coworking.”

https://axisspace.com/the-rise-of-miami-as-a-business-hub-a-journey-through-innovation-and-coworking/

- Fox Business, “South Florida cashes in on new wealth as New York City pays the price.”

- Fraud / public‑fund mismanagement and corporatism context

- Inside SALT (Bloomberg Tax), “California faces new proposed wealth tax.”

https://www.insidesalt.com/2025/11/biting-the-hand-that-feeds-california-faces-new-proposed-wealth-tax/ - New York Post, “California AG admits ‘billionaire tax’ would sink state revenues as advocates cleared to gather signatures.”

https://nypost.com/2025/12/31/us-news/california-admits-billionaire-tax-would-sink-state-revenues-as-advocates-cleared-to-gather/

- Inside SALT (Bloomberg Tax), “California faces new proposed wealth tax.”

- Tweets and threads referenced

- David Sacks urging YC to open in Austin.

https://x.com/DavidSacks/status/2005194733744951457 (example from your screenshot) - Garry Tan on unrealized‑gains tax and YC leaving California.

https://x.com/garrytan/status/2005109164271698041 (example from your screenshot) - Aakash Gupta thread arguing SF and NYC remain dominant tech/finance hubs.

https://x.com/aakashgupta/status/2006819931907067985 (example from your screenshot)

- David Sacks urging YC to open in Austin.

- Historical failures of confiscatory policy

- General background on Soviet economic planning and collapse; discussion in Investopedia piece above and standard economic histories.

- New York Post and related reporting on California’s revenue warnings under the billionaire tax.

https://nypost.com/2025/12/31/us-news/california-admits-billionaire-tax-would-sink-state-revenues-as-advocates-cleared-to-gather/